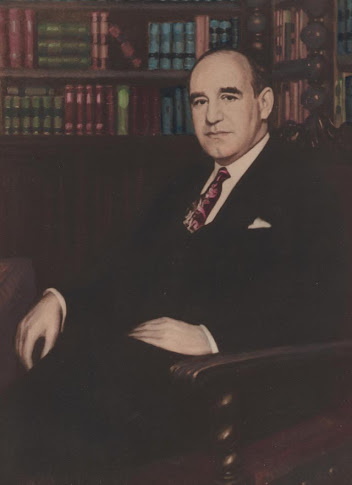

In the September, 1925 issue of Conrado W. Massaguer's magazine "Social" he featured an article written by Gustavo Gutiérrez entitled "The need for a new world," (La necesidad de un mundo nuevo). Gutiérrez was 29 years old. As the title states Gutiérrez is concerned with the state of affairs in a world ravaged by a world war and the need for international law and justice especially in a modern, interdependent and violent world where communication and connectivity has increased with the advent of international commerce, aviation and telecommunications.

He reminds us that war leads to more aggression and only through legal judicial means can civilization attempt to live in peace and harmony. If we were able to discover the New World behind a terrible cordon of fire and create a document in defense of "The Rights of Man and Citizen," destroying the divine rights of kings that the church protected, then why can't we learn to organize the world and thus, avoid wars? Just like Cro-Magnon man, the ancients of Rome or the Spaniard of King Phillip II were unable to envision the marvels of our modern society, we can not act in arrogance in relation to what our future may bring. Great men of every age have brought us glorious things, planted seeds of invention and ideals that grow and flower, repeating this cycle, stupendous and incessant. But for now the immediate problem is the question of peace. For if we abandon the harvest of illumined men for that of spilled blood and gold as a means for achieving harmony, we will once more hear the noise of war machines and witness yet again the formidable crashing of armies until that time when we can collect the fruits of our harvest, late perhaps, that we call international law, whose laborious gestation results so costly for the progress of humanity and civilization.

He quotes in his essay French philosopher Rousseau, Renault, Pillet, James Lorimer and English author of international public law, Lord Phillimore.

He reminds us that war leads to more aggression and only through legal judicial means can civilization attempt to live in peace and harmony. If we were able to discover the New World behind a terrible cordon of fire and create a document in defense of "The Rights of Man and Citizen," destroying the divine rights of kings that the church protected, then why can't we learn to organize the world and thus, avoid wars? Just like Cro-Magnon man, the ancients of Rome or the Spaniard of King Phillip II were unable to envision the marvels of our modern society, we can not act in arrogance in relation to what our future may bring. Great men of every age have brought us glorious things, planted seeds of invention and ideals that grow and flower, repeating this cycle, stupendous and incessant. But for now the immediate problem is the question of peace. For if we abandon the harvest of illumined men for that of spilled blood and gold as a means for achieving harmony, we will once more hear the noise of war machines and witness yet again the formidable crashing of armies until that time when we can collect the fruits of our harvest, late perhaps, that we call international law, whose laborious gestation results so costly for the progress of humanity and civilization.

He quotes in his essay French philosopher Rousseau, Renault, Pillet, James Lorimer and English author of international public law, Lord Phillimore.