Gustavo y otros oficiales en la reunion con representantes de la Mision Económica de las Naciones Unidas. Gustavo era presidente de la Junta Nacional de Economía bajo el Presidente Carlos Prio.

Gustavo firmando La Carta de La Habana por Cuba con el representante estadounidense William Clayton durante la clausura de La Conferencia De Comercio también conocido en ingles como el G.A.T.T. (General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs).

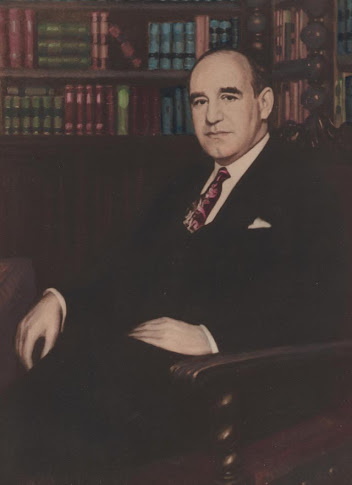

GUSTAVO GUTIERREZ: ESTADISTA CUBANO

En agosto de 1953 el Dr. Gustavo Gutiérrez y Sánchez aceptó el cargo de Ministro de Hacienda. Veinte meses antes Batista había intentado reclutar a Gutiérrez para el cargo de Ministro de Estado en la madrugada de aquel fatídico 10 de marzo de 1952. Gutiérrez, furioso por el golpe de Batista, rechazó el puesto ministerial. Gustavo era en ese momento presidente de la Junta Nacional de Economía, cargo que ocupaba bajo el recién derrocado presidente Carlos Prío.

Elperiódico Información dijo lo siguiente sobre el nuevo cargo de Gutiérrez como ministro de Hacienda: "Sin temor a equivocarnos, nos atrevemos a decir que su capacidad lo ha impuesto. Individuo de profundos conocimientos en materia social, financiera y hacendistica hace ya algun tiempo que, sin bombos ni platillos, pero de manera incansable y altamente eficiente, viene dando a Cuba lo mejor de sus esfuerzos e inteligencia desarrollando una labor que pocos pueden igualar en nuestro pais, en cualquier tiempo. Y hay que tener en cuenta, al hacer un análisis de su ingente labor, que siempre han sido llamado en momentos de graves crisis en los departamentos bajo su mando, y que siempre ha salido airoso en sus empeños dejando bien plantada la fe puesta en él por quienes en él confiaron.Enemigo de los zigzagueos, rectilíneo en sus procedimientos, honesto, mesurado y siempre justo y sereno, Gustavo Gutiérrez podría insertar en su heráldica la famosa frase: "animo et fide"; Valor para hacer frente a toda situación difícil, resolviéndola; y fe en sí mismo, en su capacidad, en sus arrestos, en su valiosa personalidad.Convencidos de la enorme potencialidad constructiva y organizadora del actual Ministro de Hacienda, aseguramos que con un puñado de “Gustavos” Gutierrez, Cuba saldría como por arte de encantamiento, de todas las dificultades que actualente obstaculizan su más rápido progreso social y económico y que él casi solo, pero decidido y lleno de entusiasmos, va salvando desde el alto puesto que desempeña a satisfacion de toda la ciudadanía." Conrado Massaguer escribió en la misma época: "...Gustavo, actual embajador, tiene un sólido nombre entre los abogados, los literatos y los internacionalistas".

Nacido en Camajuaní, provincia de Las Villas, en 1895, e hijo de un exitoso tabaquero inmigrante español y de la hija de un gobernador provincial. Los padres de Gustavo trasladaron a la familia a La Habana en 1900, donde Gustavo estudió en el Instituto de La Habana, el colegio jesuita de Belén, y luego obtuvo un doble doctorado en Derecho Civil y Derecho Público en la Universidad de La Habana. En 1919 se convirtió en profesor de derecho internacional y luego se incorporó al prestigioso bufete del Dr. Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante. Permaneció como miembro del profesorado universitario hasta 1934, cuando fue destituido como resultado de una depuración del profesorado por el nuevo gobierno a causa de su colaboracion con el Presidente Machado y el Partido Liberal.

Se unió a Los Minoristas, un grupo de jóvenes intelectuales que se autodenominaban "nacionalistas, progresistas, vanguardistas y antiintervencionistas!" Fue invitado por el Presidente José Miguel Gómez a unirse al movimiento político conocido como Los Veteranos y Patriotas, donde el Comité de los Cinco declaró a Gustavo "la voz de oro" por sus elocuentes y apasionados discursos. Ambos grupos influenciaron la politica de Gustavo, profundamente.

Fue en esta época, a principios de los años 20, cuando Gustavo fue elegido como enlace del gobierno para la construcción tanto del majestuoso edificio del Capitolio, construido por Purdy y Henderson, como de El Hotel Nacional, diseñado por McKim, Mead y White, debido a su excelente conocimiento del derecho internacional y su buen dominio del idioma inglés. Ambos eran empresas estadounidenses. En 1925, el presidente Machado le nombró consejero legal del Ministerio de Estado, siendo el primer cargo gubernamental de Gustavo. Nunca más abandonaría el servicio público.

Gustavo comenzó a viajar a conferencias internacionales con dignatarios como Orestes Ferrara y Ramiro Guerra, igual que alcanzando notoriedad como abogado y autor internacional. Sus obras publicadas fueron aclamadas internacionalmente, lo cual le valió el título de Honoris Causa. En 1929, el intelectual cubano Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring escribió en la revista Carteles: "Orador elocuente, autor profundo, luchador infatigable, este joven, Gustavo Gutiérrez, es uno de los más valientes representantes en el mundo de la política y de los intelectuales, de quien puede decirse merecidamente que el futuro le pertenece."

El 26 de junio de 1933, después de haber consolidado su reputación como experto en derecho público y asuntos judiciales, el profesor universitario Gustavo Gutiérrez, a los 37 años de edad, fue nombrado Secretario de Justicia por el presidente Gerardo Machado. Este fue un honor trascendental para Gustavo. En su discurso de aceptación, es interesante destacar que Gutiérrez mencionó a una gran variedad de pensadores e intelectuales políticos y jurídicos de la época, entre ellos; Del Vecchio, un reconocido intelectual fascista; Henri Levy-Ullman, experto en el sistema de tribunales inglés y Benedetto Croce, entre los intelectuales liberales más importante de Italia del siglo XX. Estos y otros habían influido a Gustavo, que se perfilaba como hombre de síntesis. Era un lector voraz que asimiló un amplio abanico de filosofías e ideas políticas a partir de las cuales se formó su particular visión, que le serviría para el resto de su carrera profesional.

Debido al creciente descontento político y popular contra el presidente convertido en dictador, Gerardo Machado, Gustavo renunció habiendo durado sólo 38 días en el cargo. Varios años antes había aconsejado a Machado que no manipulara la Constitución vigente, que Machado pretendía modificar, para reelegirse. En sus memorias, la esposa de Gustavo, María Vianello, escribió que Machado, queriendo un segundo mandato, solicitó una reunión con dos eminentes abogados Octavio Averoff, Ricardo Doltz y el joven Gustavo Gutiérrez. Los dos primeros estuvieron de acuerdo con el plan de Machado. Sin embargo, Gustavo respondió: "Señor Presidente, soy de la opinión de que no deba reelegirse". Machado no esperaba semejante respuesta de Gustavo cuya familia conocía íntimamente desde antes del nacimiento del mismo. Según los cuentos familiares, Machado fue el primer miembro no familiar que cargo al bebé Gustavo en sus brazos. Machado golpeó la mesa con el puño y replicó: "¿Y pensar que tú, entre todas las personas, te opones a mi decisión? Tú a quien llevé en brazos cuando naciste y a quien he querido tanto". Gustavo replicó: "No haga algo de lo que se va a arrepentir gravemente".

Tras el derrocamiento de Machado, el Partido Liberal, el partido político de Machado y Gustavo, fue abolido y sus miembros condenados al ostracismo de la vida pública. Muchos colaboradores inclusive fueron asesinados por las turbas enloquecidas. El presidente interino, Dr. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, convocó a Gustavo para que le asesorara sobre la crisis constitucional. Gustavo cruzó la ciudad para reunirse con de Céspedes y aceptó asesorar sobre la crisis. Su única petición fue la clemencia para los funcionarios de Machado. Su petición fue concedida, pero las multitudes enfurecidas tenían en mente una violenta venganza. Este hecho resultó en cientos de asesinatos políticos por toda la isla y la peor ola de incendios y saqueos que la joven república había presenciado jamás. Gustavo estaba desolado por el giro destructivo de los acontecimientos y por el comportamiento salvaje que habían perpetuado tantos cubanos, una realidad que pocos olvidarían, incluido Gutiérrez.

Tras ser destituido de su puesto de profesor universitario y condenado al ostracismo por las nuevas élites políticas por sus asociaciones con la dictadura de Machado, Gustavo se recluyó en su biblioteca y comenzó a escribir y a aceptar los trabajos que podía. Se unió a Ramón Vasconcelos, un respetado periodista y líder del Partido Liberal, y juntos redactaron los estatutos del nuevo Partido Liberal y sus nuevas directrices, el Manifiesto-Programa, en octubre de 1934.

Poco después, en 1936, Gustavo Gutiérrez fue elegido por ambas cámaras del Congreso para redactar una nueva constitución, un honor extraordinario para cualquier hombre de su profesión. Su proyecto fue más extenso que el modelo constitucional promedio debido principalmente a que, como él mismo declaró, "Mi experiencia como jurista y político me ha convencido de que el derecho constitucional, en países como el nuestro que aún no han alcanzado la madurez política, no puede ser una simple declaración de principios que luego evolucione a través de la legislación, las costumbres y en la práctica, con absoluto respeto a las normas fundamentales." Intuyó la necesidad de "explicitarlas cosas" con mayor detalle, precisión y claridad. Temía, por ejemplo, que ni la legislación del Congreso ni el presidente en funciones pudieran resistir la gran presión ejercida sobre ellos por los poderosos intereses privados "afectados". Creía que había que tener más cuidado con la relación asimétrica entre el poder ejecutivo, siendo más poderoso, y los poderes legislativo y judicial, siendo más débiles, con la esperanza de no repetir las mismas omisiones y carencias que entorpecieron a los redactores de las dos primeras constituciones cubanas.

Uno de los principales ingredientes que eludieron las reformas constitucionales anteriores estaba relacionado con los derechos de las masas humanas enfrentadas por el rápido y desigual crecimiento mundial del capitalismo y la industrialización. Esta omisión histórica y la preocupación de Gustavo por la "interdependencia social" serían componentes importantes para su proyecto. Así, escribió en esa época: "Los que no estamos satisfechos ni con el Estado "liberal democrático" según la vieja escuela de pensamiento inglesa ni con el modelo de Estado "proletario" introducido por el sistema soviético, aceptamos del modelo de Estado "individualista" (al que los socialistas marxistas se refieren en términos despectivos como Estado "burgués) la necesidad de proteger la libertad individual para no caer en la esclavitud a merced del modelo socialista. Respetamos la existencia de la propiedad privada pero no en el antiguo concepto romano del derecho, donde su uso y abuso beneficiaba exclusivamente al propietario de la tierra, sino para el bienestar social de todos." El deseo de Gustavo era fusionar una constitución individualista con una constitución socialista, libre de una agenda marxista, abarcando una mezcla de ambas; de naturaleza elástica y convergente en algún punto intermedio consistente en principios y "leyes fundamentales que avancen en un sistema de garantías individuales y sociales".

El 13 de febrero de 1939, en preparación para la creación de esta nueva constitución, la asociación profesional afrocubana, El Club Atenas, invitó a los líderes de los principales partidos políticos a exponer sus plataformas políticas y puntos de vista sobre el trabajo, la educación pública, la inmigración, la economía y la discriminación racial. Gustavo Gutiérrez, que había sido elegido diputado el año anterior, fue elegido por el Partido Liberal para presentar su plataforma al club.

El Partido Liberal era el partido de la mayoría de los dirigentes de El Club Atenas y de la población negra en general. Sus intelectuales más importantes y los generales y militares de la Guerra de la Independencia eran miembros del Partido Liberal. Además, el ex presidente del Partido, Gerardo Machado, era el que más había hecho hasta la fecha por la clase pobre y trabajadora de Cuba, muchos de ellos negros. No sólo había proporcionado al Club Atenas la propiedad sobre la que se construyó el Club, sino que Machado había solicitado al Congreso la donación de los fondos para levantar su edificio. Gustavo decidió abordar el tema que más afectaba e interesaba a la población negra en Cuba, la discriminación racial. Este fue uno de los discursos más esperados de los quince que se programaron, así como, uno de los mejor recibidos.

El 21 de noviembre de 1940, Gustavo Gutiérrez fue elegido Presidente de la Cámara de Representantes. Una vez más estuvo eufórico de servir al país que tanto amaba. Pero, de nuevo, el destino se interpuso. Después de un año en el cargo, renunció. Un recorte de prensa de ese día decía: "El profesor Gustavo Gutiérrez, al renunciar a la presidencia de la Cámara, presentó su renuncia como "irrevocable" por la falta de cooperación de los congresistas." Un número insuficiente de representantes se presentaba al trabajo para votar sobre legislación pendiente.

El jurista estadounidense William S. Stokes escribió en su momento: "Los disturbios, los abucheos, las ausencias e incluso las peleas a puñetazos caracterizaron la sesión de ambas cámaras". El Dr. Gustavo Gutiérrez, uno de los más firmes y hábiles defensores del sistema parlamentario, renunció a la presidencia de la Cámara debido a la dificultad de obtener quórum y a la indiferencia general de los miembros hacia sus responsabilidades en el Congreso. "El único recurso de Gustavo ante tal intransigencia fue renunciar.

Irónicamente, una de las únicas propuestas legislativas importantes que se convirtieron en ley durante ese turbulento período fue el propio Código Electoral de 1943 de Gutiérrez, creado en 1936 y convertido en ley en 1941. Llamado El Código Gutiérrez por el Dr. Elio Fileno de Cárdenas, miembro de la Comisión del Código Electoral del Senado, escribió: "Fue creado para defender el sufragio universal y promover el proceso democrático codificando el proceso electoral, implementando un sistema electoral sólido, organizando y haciendo permanente el procedimiento y el proceso de votación, respectivamente, frenando las irregularidades de la votación y reduciendo el fraude electoral, etc.".

Carlos Márquez-Sterling, un viejo amigo que sustituyó a Gustavo como presidente de la Cámara, añadió que el nuevo Congreso se había duplicado en tamaño sin aumentar su presupuesto anual. Escribiría décadas después: "Por todo esto, Gustavo quedó curado de su anhelo político y sin dejar la vida pública, se retiró al ejercicio de otras actividades más acordes con sus condiciones intelectuales, que eran muy variadas, y muy brillantes en el campo de la economía al que se había ido acelerando cada día más..." Su hija Yolanda estaría de acuerdo añadiendo que su padre carecía de la duplicidad habitual en la política, le disgustaba la desorganización y era un hombre de palabra. Aborrecía la ineficiencia y la dilación y era conocido por sus bruscos ataques de ira, que provocaban olas de pánico en la oficina y en el hogar.

Cuando dejó la Cámara de Representantes en 1942, Gustavo Gutiérrez abandonó la política para siempre, al darse cuenta de que su temperamento no combinaba bien con la "política de siempre". Su experiencia como Secretario de Justicia en los últimos meses del Machadato y como Presidente de la Cámara durante una conflictiva transición en el Congreso le "abrió los ojos" a la inmadurez e irresponsabilidad del hombre en los más altos niveles del gobierno. Reconoció que la mejor manera de seguir sirviendo a su país era a través de la economía y las finanzas, donde su enfoque se desplazaría hacia el desarrollo social y económico. Aquí podría marcar la diferencia con poca o ninguna interferencia por parte de hombres de poca monta. El economista Luis José Abalo dijo en su momento: "Gustavo Gutiérrez no fue economista hasta que comprendió que podía prestar un mayor servicio a su país en el campo estruendoso y dinámico de la economía en lugar de la atmósfera absorbente y cautelosa del derecho y la política."

En 1942 Gustavo se convirtió brevemente en presidente de la incipiente Comisión Marítima de Cuba, donde aumentó la cantidad de buques comerciales cubanos, evitando así que el gobierno cubano dependiera de los buques estadounidenses para transportar el azúcar cubano y otras exportaciones. Esto facilitó un ahorro de millones de dólares anuales para la isla. Al renunciar a este cargo, una publicación nacional afirmó: "Cuando a finales de marzo de 1943 cedió su puesto al Dr. Santos Jiménez, los representantes de todas las instituciones y organizaciones relacionadas con las clases económicas, en cálidos discursos y manifestaciones, expresaron su profunda tristeza por la renuncia (de Gutiérrez) a la presidencia de la Comisión Marítima de Cuba." Ese mismo año organizó y asumió la presidencia de la Junta de Economía de Guerra para bregar con los afectos producidos por la guerra en Europa. Esta se convirtió en la Junta Nacional de Economía donde Gustavo llegó a ser secretario bajo el presidente Grau, director técnico y luego presidente bajo los presidentes Prío y Batista.

A mediados y finales de la década de 1940, Gustavo ejerció sus diversas capacidades en el ámbito de la diplomacia internacional, principalmente en las Naciones Unidas. En 1943, encabezó la delegación cubana ante la Administración de Socorro y Rehabilitación de las Naciones Unidas (UNRRA) en Atlantic City y fue nombrado Presidente del Subcomité de Asistencia Política a las Poblaciones Desplazadas, uno de los comités más importantes y difíciles encargados de remediar la devastadora crisis de refugiados humanos en la Europa desgarrada por la guerra.

En 1945 publicó La Carta Magna de la Comunidad de las Naciones (Vol. 1), un impresionante tomo de 587 páginas que se trata de "la historia de la constitucionalidad del hombre". En el prólogo, el magistrado de la Corte Internacional de Justicia, Dr. Antonio S. de Bustamante, escribió: "Nuestro bien conocido internacionalista, el Dr. Gustavo Gutiérrez, pone una ves mas de relieve en este libro, no sólamente su notoria competencia cientifica, sino ademas su alto sentido social y jurídico frente a los graves problemas que el termino proximo de la segunda guerra mundial de este siglo necesitan afrontar y resolver las naciones aliadas.”

De este trabajo la delegación cubana extrajo una gran parte de su borrador para la creación de la Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos, que Cuba presentó en la sesión inaugural de las Naciones Unidas en San Francisco en 1945. Además, Gutiérrez redactó de forma independiente uno de los siete borradores privados que se utilizaron para la creación de la Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos, quizá su mayor logro judicial. John P. Humphrey preparó el primer borrador de la Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos en 1947. Escribió: "Yo no era ningun Thomas Jefferson y, aunque era abogado, prácticamente no tenía ninguna experiencia en la redacción de documentos. Pero como la Secretaría había reunido una veintena de borradores, tenía algunos modelos sobre los cuales trabajar. Uno de ellos había sido preparado por Gustavo Gutiérrez y probablemente había inspirado el proyecto de Declaración de los Deberes y Derechos Internacionales del Individuo, que Cuba había patrocinado en la Conferencia de San Francisco.” Es a partir del capítulo 25 de La Carta Magna de Gutiérrez que se pueden encontrar los Deberes y Derechos Internacionales del Individuo.

En 1947, Gustavo fue nombrado Presidente del Comité de Redacción Jurídica por las Naciones Unidas y director técnico de parte de la delegación cubana para la creación del G.A.T.T. (Acuerdo General de Comercio y Aranceles) en Ginebra, Suiza, como parte de la O.I.C. (Organización Internacional del Comercio). Fue un esfuerzo monumental de parte de todas las naciones para equilibrar el comercio internacional y reformar el sistema arancelario, que había beneficiado predominantemente a las naciones industriales. Cuando el GATT llegó a su inevitable conclusión, Gustavo Gutierrez ascendió a la presidencia de la delegación cubana, y cuando Cuba acogió la última Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Comercio y Empleo para crear la O.I.C., en 1948, Gustavo fue el anfitrión de la conferencia internacional y recibió el honor de firmar la Carta de La Habana para Cuba.

Al final de su discurso de 11 páginas dirigido a todas las naciones reunidas en La Habana, Gustavo dijo: "En Ginebra nos llamó la atención una placa de bronce, que recuerda al transeúnte que hace más de dos mil años, César, pasó por allí en su camino para conquistar a los bárbaros que habitaban la Galia. Mañana, en este país, que hace sólo cuatro siglos y medio era un paraíso de salvajes felices y amables, se firmará la Carta de la Organización Internacional del Comercio. César ha seguido su camino y la Galia es ahora uno de los países más civilizados del mundo, pero el nombre de Ginebra sigue siendo un símbolo de paz y libertad. Tú también seguirás tu camino y la soleada tierra de los indios siboney y taínos continuará su progreso, hasta convertirse también en una de las naciones más famosas del mundo. Que el amable nombre indio de La Habana, bajo cuya protección descansa ahora la bienintencionada Carta de la Organización Internacional del Comercio, sea para todos un talismán de buena voluntad, progreso y prosperidad."

Ese mismo año, Gustavo se convirtió en embajador extraordinario y representante suplente cuando Cuba entró en el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas como miembro rotatorio, un gran honor para cualquier país. Las Naciones Unidas estaban inmersas en las decisiones cruciales de admitir a España y al recién creado estado de Israel en la organización. Gutierrez y la delegación cubana estuvieron en el centro de estas tormentas políticas y diplomáticas.

En 1949, Gutiérrez se convirtió en presidente de la delegación cubana en las Naciones Unidas y, al año siguiente, se encontro en la ofenciva, acusando al embajador soviético Andrei Vishinski delante de la Asamblea General de comportarse como un prestidigitador de feria. Al parecer, Gutiérrez fue el único diplomático que cuestionó las declaraciones de Vishinski sobre la invasión china en Corea. El embajador soviético había sido el fiscal principal de Stalin durante la Gran Purga de los años 30 y era muy temido en su país. El periódico Avance afirmó que "Gutiérrez es uno de los pocos delegados en las Naciones Unidas, quizás el único, que ha destruido el argumento pseudojurídico de Vishinski" y ante un público atónito Gutiérrez expuso la fantástica falsificación de textos legales de parte del delegado soviético. Se convirtió en una causa célebre entre los diplomáticos occidentales.

En 1951, tal vez como recompensa por parte de los paises aliados por su valentia, fue nombrado Presidente del Comité Económico de las Naciones Unidas. A lo largo de la década de 1950 representó a Cuba en numerosas conferencias internacionales y hemisféricas sobre comercio, aranceles, desarrollo económico y finanzas. Viajó a Ginebra, Río de Janeiro y Petrópolis, Buenos Aires, Ciudad de México, Ciudad de Panamá, Santiago de Chile, Washington y Nueva York, entre otros.

Entre 1948 y 1953 Gustavo trabajó como secretario, director técnico y luego presidente de la Junta Nacional de la Economía (JNE), donde dirigió numerosos proyectos. Uno de ellos fue la creación de un instituto que proporcionara las estadísticas que se necesitaban urgentemente en relación con el consumismo, la distribución de los ingresos nacionales y los datos estadísticos esenciales y críticos de los cuales Cuba carecía. También fue uno de los jefes de comité en las negociaciones entre Cuba y el Banco Internacional de Reconstrucción y Desarrollo, una misión económica dirigida por Francis A. Truslow. Los resultados produjeron un informe de 1.100 páginas que enumeraron recomendaciones para el desarrollo económico de Cuba. Este informe fue de suma importancia para Cuba, ya que proporcionó una gran cantidad de información, sugerencias y orientación.

El 10 de marzo de 1952, Gustavo fue despertado por una llamada telefónica a las 4 de la mañana. Al otro lado del teléfono estaba Justo Luis del Pozo, antiguo alcalde de La Habana y colaborador de Batista. Las palabras que pronunció a través del receptor telefónico enfurecieron a Gustavo. "¡Qué horror! Hemos retrocedido 50 años de Republica", gritó aquella fatídica mañana, caminando de un lado a otro en pijama frente a su habitación. Gustavo estaba furioso porque horas antes Batista había dado un golpe de estado contra el presidente Carlos Prío. La llamada de Del Pozo fue para informarle a Gustavo que Batista le quería en su gobierno, ofreciéndole el codiciado puesto de Ministro de Estado. Gustavo le gritó al Sr. del Pozo que no era la hora adecuada/apropiada para llamar por teléfono a casa de alguien y, al mismo tiempo, rechazó enfaticamente la oferta de Batista.

Aquella mañana convocó apresuradamente a su hija Yolanda a su biblioteca y le dijo: "Lo que ha hecho este hombre no tiene nombre . Nos ha dejado sin Constitución y ahora tendrá que gobernar mediante estatutos. Siéntate y teclea lo que voy a decir". Una joven de 26 años, Yolanda no estaba muy segura de lo que su padre estaba gritando, pero sabiendo que nunca debía cuestionarlo, se mantuvo callada mientras Gustavo procedía a dictar los estatutos sobre los que se iba a rejir la nación. El documento fue enviado inmediatamente al Palacio Presidencial.

Batista, que temía que Gustavo abandonara el gobierno en protesta por el golpe de estado, le animó a unirse a su administración poco después de tomar el poder. Batista convenció a Gutiérrez que aceptara el título de Ministro sin Cartera porque queria que Gustavo formara parte de su Consejo de Ministros. A cambio, Batista se comprometió a elevar la influencia y el estatus de la Junta Nacional de Economía. Batista quería a Gutiérrez en su gobierno a todo costo. Como presidente de la JNE, Gutiérrez escribió varias obras importantes sobre la economía cubana y dirigió un ambicioso proyecto para estimular y diversificar rápidamente la agricultura y la industria cubana y crear empleo, al tiempo que reformaba los derechos de la aduana y las políticas fiscales.

No fue hasta un año y pico después, en agosto de 1953, que Gustavo aceptó el nuevo cargo de Ministro de Hacienda. Batista le pidió ansiosamente a Gustavo que aceptara el puesto debido a las irregularidades en el ministerio. Muchos periódicos saludaron este nombramiento como un triunfo para el futuro de Cuba, colmando de elogios a Gutiérrez. Su primera tarea fue reorganizar la Tesoreria Pública, que se encontraba en un estado vergonzoso y desorganizado, así como, cuadrar los libros, donde descubrió muchas discrepancias. Encabezó la compra de las tierras a los británicos por las cuales circulaban los ferrocarriles en la isla. Corrigió los "despilfarros de antaño", cuestionó los "irritantes privilegios de casta", así como, acabó con los dudosos "fondos especiales" que disponia la rama ejecutiva. Gustavo expuso estos detalles a su antiguo amigo Ramon Vasconcelos en el periodico Alerta. Facilitó los pagos atrasados del gobierno a los proyectos de obras públicas, al sector de servicios y a los intereses azucareros y, junto con el conocido arquitecto Nicolás Arroyo, dirigió el ambicioso Plan de Desarrollo Económico y Social. Además, Gutiérrez había llegado a supervisar, como ministro de Hacienda, la mayoría de los programas de obras públicas del gobierno de Batista, para disgusto de otros ministros del gabinete.

A finales de 1954 Gutiérrez dejó el Ministerio de Hacienda debido a desacuerdos con Batista, para crear el de facto Ministerio de Economía, el Consejo Nacional de Economía, (CNE), como unica manera de continuar en el gobierno de Batista. El propósito del CNE era asesorar a Batista y a su gabinete en todo lo relacionado con la economía nacional. Creado el 27 de enero de 1955, su objetivo declarado era "orientar y coordinar la política económica del gobierno y crear altos niveles de empleo y productividad". Gutiérrez estuvo al frente de este ministerio durante cuatro años y, según el CERP, "la función de la CNE era orientar y coordinar las medidas, planes, programas y políticas destinadas a proteger y fortalecer la economía de la isla, especialmente frente a las contracciones internacionales o nacionales". La CNE produjo una importante cantidad de folletos y libros, además del uso innovador de la econometría. Uno de los estudios de Gutiérrez, "Empleo, Subempleo y Desempleo", causó un gran revuelo en los círculos gubernamentales y empresariales por sus revelaciones y advertencias sobre el subempleo, un dilema tóxico y crónico entre las naciones latinoamericanas.

En1956, Gutiérrez se convirtió en presidente de la recién creada Comisión de Energía Nuclear de Cuba y presidente de la Comisión Ministerial para la Reforma Arancelaria en 1958. En este periodo, Gustavo Gutiérrez también encabezó delegaciones cubanas en Ginebra, Panamá, Brasil y Buenos Aires para conferencias hemisféricas sobre finanzas, empleo y desarrollo económico. En Petrópolis se dirigió a los delegados reunidos: "Los países de América Latina no podemos buscar exclusivamente en el exterior las soluciones a nuestros problemas. Creemos que el desarrollo económico de un país depende fundamentalmente tanto de su propio esfuerzo como de sus recursos naturales. Nuestro país practica el principio del autodesarrollo. Utilizando exclusivamente nuestros recursos económicos y financieros hemos construido más de 4 000 kilómetros de calles y carreteras secundarias, cientos de autopistas y varios acueductos y hospitales; hemos adquirido los Ferrocarriles Unidos de La Habana a sus propietarios ingleses y los hemos rehabilitado; estamos dragando nuestros puertos; estamos construyendo la primera central hidroeléctrica y proyectamos el establecimiento de plantas de glicerina y papel a partir del bagazo de la caña de azúcar; hemos organizado la Agencia Nacional de Finanzas, el Banco Cubano de Comercio Exterior y estamos organizando el Instituto Cubano de Investigaciones Técnicas; estamos revisando nuestros aranceles para proteger el desarrollo económico de nuestro país.”

El 1 de enero de 1959, Gustavo se despertó con la noticia de que Batista había huido de Cuba dejando un vacío de poder y creando un pandemónium en toda la isla. Como había sido un funcionario honesto y ético y nunca había cometido delitos contra el Estado, rechazó los consejos de sus familiares y amigos de pedir asilo en una embajada. Sin embargo, el caos en el que se sumió La Habana cuando las fuerzas castristas entraron en la ciudad fue testigo de cómo se encarcelaba e incluso se ejecutaba a personas inocentes. Gustavo recordaba el estado de anarquía en el que se había sumido la nación tras la revolución de 1933 y esperaba que no se produjera la misma anarquía y búsqueda de venganza. Se equivocaria de nuevo. Encarcelamientos, fucilamientos, saqueos y confiscaciones de propiedades marcaron la llegada de los liberadores barbudos. Muchas embajadas estaban siendo atacadas repetidamente por furiosos partidarios de Castro que intentaban sacar a sus asilados.

Después de discutir durante horas con sus hijas y amistades, cedió y entró en la embajada argentina con la estipulación exacta de que sólo aceptaría, directamente del embajador, una invitación personal para visitar la embajada como ciudadano particular y no como personaje público que pide asilo. Despues de dos semanas hacinado en una pequeña habitación con otros 4 hombres, voló a Buenos Aires, el 16 de enero.. Le acompañaban Eusebio Mujal, presidente de la CTC, el sindicato más poderoso de la isla, y Justo García-Rayneri, antiguo ministro de Hacienda y miembro del gabinete de Batista.

Dado que el Departamento de Estado de EE.UU. había emitido una "lista negra" de funcionarios y colaboradores de Batista que se contaban por cientos, a Gustavo no se le permitió la entrada en Estados Unidos. Tras esperar casi 6 meses en Argentina, fue operado de un tumor canceroso. Acosado por unas fiebres persistentes, voló a Ciudad de México para estar más cerca de su familia. Por fin, a finales de junio, llegó su visado y se le permitió entrar en Estados Unidos. Voló urgentemente a Miami e ingresó inmediatamente a Mercy Hospital donde los cirujanos descubrieron una esponja quirúrgica infectada que no se había retirado mientras estaba en Buenos Aires.

Gustavo Gutiérrez murió en Miami el 17 de julio de 1959. Su cuerpo fue trasladado a La Habana tras recibir el permiso del nuevo gobierno cubano y enterrado en el Cementerio Colón. Pocos fuera de la familia inmediata asistieron a su funeral por miedo a las recriminaciones del nuevo gobierno. Sus cuatro hijas, sus maridos y sus hijos, pronto abandonarían Cuba para no volver para siempre. María permaneció en La Habana hasta 1965.

Las propiedades de Gustavo fueron confiscadas poco después de que saliera de Cuba. Al año siguiente, después de que el régimen castrista investigara y, al constatar que Gutiérrez no había amasado riquezas ni cometido ningún delito contra el Estado, fue exonerado y declarado públicamente "Persona No Malversadora" por el Ministerio de Recuperación de Bienes Malversados. Sus propiedades y su contenido fueron devueltos a su esposa María.

Su vida personal y familiar sufrió debido a su obsesión por sus deberes cívicos; asistiendo a reuniones gubernamentales que duraban hasta altas horas de la noche, viajando a conferencias internacionales durante meses o enclaustrándose en su biblioteca leyendo y escribiendo durante horas. En su lecho de muerte se disculpó con María por no asistir a más reuniones familiares y por cuestionar la existencia de Dios, confesándole: "¿Crees que me perdonará?" Las lágrimas corrían por sus mejillas y Maria respondió enfáticamente: "¡Sí, te perdonará!"

Gustavo Gutiérrez fue un hombre dedicado al pueblo y a una Cuba próspera. Toda su vida la dedicó a estos fines en el sector público, asumieno puestos en los que podía aplicar sus conocimientos y experiencia en beneficio del bienestar social, económico y político de esta joven nación isleña. Creó legislacion para el bien común que beneficiaban al pueblo cubano como: una ley que organizó todas las bibliotecas de Cuba; una ley que creó la Biblioteca Nacional y el Archivo Nacional, una ley que creó el Día del Libro; una ley que modificó la caja de pensiones de las Fuerzas Armadas; una ley de pensiones para los trabajadores provinciales y municipales y una para los empleados electorales y del censo; el célebre Código Electoral de 1943, el proyecto para la creación de la Constitución de 1940; uno de los siete proyectos elegidos para la creación de la Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos; la ley que creó el Instituto de Artes Plásticas; la ley para la creación de La Casa de Las Américas; la ley para la creación de la Academia Cubana de Ciencias Sociales, y muchas más. Escribió más de un centenar de libros, folletos, artículos y discursos sobre una amplia gama de temas relacionados con la historia, la jurisprudencia, el derecho constitucional, las finanzas y la economía. Sus ultimos dos trabajos, interrumpidos por la revolucion de Fidel Castro, ubiesen sido entre sus mas importantes; una ley reorganizando la creciente industria turistica y una nueva reforma agraria. Gustavo Gutierrez le otorgó a Cuba y al mundo un rico tesoro de conocimientos, experiencia y pericia que regaló a bibliotecas publicas diseminados por todo el mundo.

El día antes de que falleciera, María notó lo enfermo y derrotado que se sentía Gustavo. Era el primer y único hombre al que había amado y no podía soportar ver cómo su caballero de brillante armadura se hundía a un nivel que nunca había presenciado. Maria vio un avión volando por encima de las nubes a través de la ventana de la habitación del hospital. Tratando de levantarle el ánimo y sabiendo lo mucho que le gustaba viajar, le preguntó: "Gus, mira ese avión volando. ¿Si estuvieras en ese avión a dónde te gustaría viajar?" Gustavo respondió con voz suave y débil: "A Cuba. A Cuba".

Por Gustsvo Ovares Gutierrez

Copyright 2021